Artist-in-Residence Edward Cheng: One View of Chinatown, from the Pandemic to a New Normal

Chinatown has long been plagued by injustice, underrepresentation, and xenophobia. The pandemic only heightened these issues. Even as the neighborhood returns to “normalcy,” photographer Edward Cheng still feels their weight. That's part of the reason he keeps taking pictures of the venerable neighborhood — to lighten that weight. His solo exhibition in the Pearl River Mart Soho gallery, "Tiny Grains: Chinatown Forever Changed, Forever Changing," features some of those photographs.

We had the chance to speak with the lifelong New Yorker about how his interest photography developed, where "tiny grains" comes from, and what he hopes for Chinatown.

Tell me a little about your childhood and background. Where did you grow up?

I was born and raised in NYC Chinatown. I went to P.S. 42, I.S. 131, Stuyvesant, and Brooklyn Polytech. I'm still living in my childhood home in Manhattan. I'm a New York kid who never left.

I travel a lot. I'll spend months in places like Spain, Indonesia, and Estonia. New York is always the place I go back home to. But the first thing I think of when I get back is leaving again. The joke with my friends is I'm always looking for airfare to leave New York.

Would you ever live somewhere besides NYC Chinatown?

I think about it all the time. Am I good enough to hit the reset button and be somewhere without the safety net, the routine, and the contacts I've built up. But nothing has drawn me elsewhere (yet).

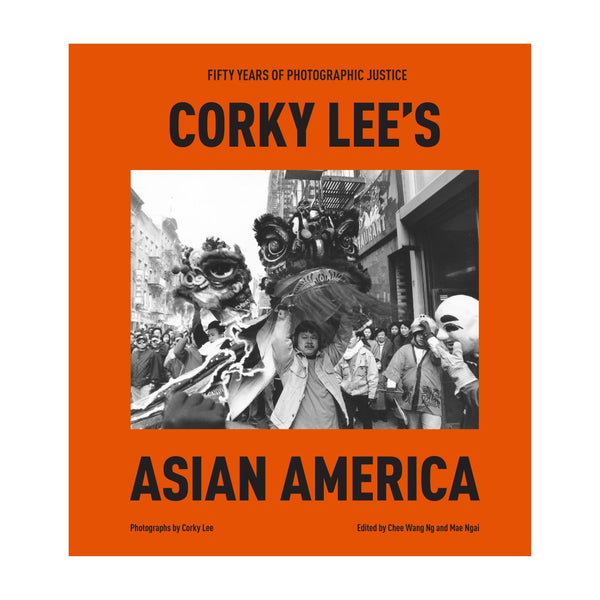

I also wonder if I weren't living in Chinatown, would I still be photographing Chinatown? I'm not sure. But there are people who still come to Chinatown to photograph it even though they don't live here. Corky [Lee] for one. Cindy [Trinh]. I'm not a gatekeeper. Just because you don't live in Chinatown doesn't mean you can't photograph Chinatown.

How did your interest in photography develop?

I started off being a stupid engineer. [Laughs] At Stuy I took a photo class, but I didn't really learn anything. I'd cut class and go play mahjong in the cafeteria. I went to school for computer science and started working as a software engineer. It wasn't until after college that a friend of mine asked if I wanted to volunteer at the International Center of Photography. That's when I started to learn everything. I also took continuing ed classes and started hanging out with people who were passionate about photography, which got me passionate about it.

My day job is still computer programming. It pays for rent and food. For things I buy from Pearl River Mart. [Laughs] I think if I were to be a full-time photographer, doing other people's projects, it would be draining.

How did the “Tiny Grains” project come about?

During the pandemic there was nothing else to do except roam the streets with my camera. And I'd always see the same people and I asked to photograph them. Then Think!Chinatown asked me to do a little slide show at one of their night markets. A slide show of what I shot in Chinatown. It was mid-2021, not too long after Corky had passed.

Then around 2022 — after the vaccines and things started to feel more normal — Arlan [Huang] said, "You should have a show. You should talk to Joanne [Kwong]. You're going to have a show."

So since then I've been working on this. I took those initial slides I put together for Think!Chinatown, and by last year I had all the images, like Chris Marte unveiling the Corky Lee Way sign. A lot of Corky is in the show. Everyone was honoring him. There's definitely a Corky throughline in the book. Corky was always in Chinatown. He was Chinatown in a way. Before the pandemic I'd see him three or four times a week. He always knew what was going on. Like when we did the lanterns [for Light Up Chinatown]. He said, "I heard they're doing lanterns. I don't know who, but let's go make a lantern."

Where does the title "Tiny Grains" come from?

I included a lot of the older generation in the book, like from the Basement Workshop. Arlan, Lillian [Huang], Henry [Chang]. It was also an opportunity to use a book spread image. The book and exhibition are called "Tiny Grains" as a nod back to that older generation who started this sense of Asian American activism. Sometimes I feel like I'm standing on their shoulders.

"Tiny grains" refers specifically to a song lyric that came about during the early days of Asian American activism in New York. treya lam was commissioned to revisit the songs from the Yellow Pearl anthology, which came out at the same time as the Basement Workshop. It also refers to the graininess of shooting on film. Grain structure. Putting those tiny grains together makes a picture. In the beginning of my book, the pictures are grainier and more fragmented. Toward the end the grains are tighter. The pictures are tighter. Each grain is also a person.

What do you hope viewers get out of your book and exhibition?

There aren't that many great pictures of Chinatown and how we do things, especially from the inside. There's no shortage of food pictures and lion dancing — I'm guilty of that too — but not a lot of other parts of Chinatown.

There was a point during the pandemic when I wondered if Chinatown would survive. Everyone was moving out. Businesses were closing. Or they didn't stay open long. I couldn't get a haircut. In fact my barber shop never reopened. Now it's just an empty storefront. Week after week places kept closing. It was heartbreaking. You kept hearing so and so is going to close. 88 Lan Zhou, Tokyo Mart, Ting's, New York Bo Ky, Lung Moon Bakery, Hop Shing. There were many points when I thought places were going to close down, including Pearl River Mart. But you guys managed somehow.

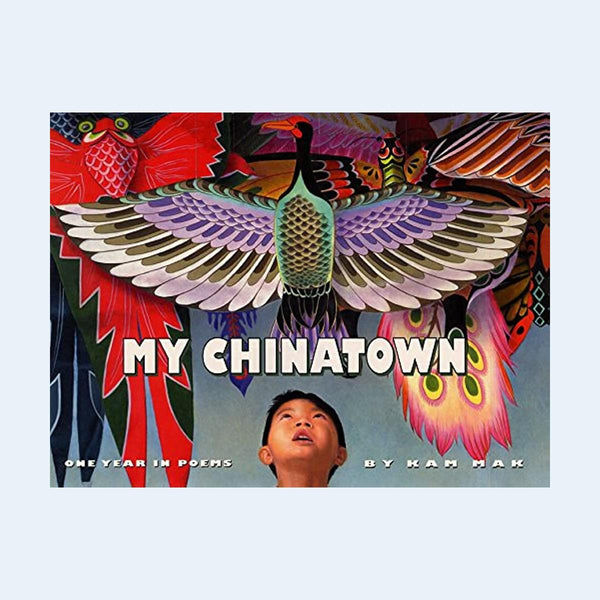

Then things started popping up. Lucy's place for instance. To be in a pandemic and open a bookshop, it was a completely weird but they did it. There was a fire and they survived again. I didn't think Jing Fong would reopen but then they did. Even with wondering if Chinatown would survive, I wanted there to be this through line of resilience in the book.

Mine is just one tiny point of view of Chinatown, one documentation of how our neighborhood did things. There's all this pandemic art coming out all over the country. In L.A. Koreatown for instance: Emanuel Hahn took pictures of all the shops and shopkeepers, and published a book of them called Koreatown Dreaming. I hope "Tiny Grains" invites a dialog with other photographers like that.

I hope the photography goes beyond the neighborhood. I was afraid that it would just be a yearbook. Chinatown is like high school in a way with cliques. The first question people ask is, "Am I in the book?" I have to say no sometimes because I'm trying to create a narrative. I hope people outside of the community would still appreciate this unique time. I hope the pictures convey that.

What do you hope for Chinatown?

I hope it survives for another 150 years at least. I hope it doesn't go the way of other Chinatowns where it's just a shell. I hope there's always going to be an active community with businesses and people living there. Of course it will change, but I just hope it survives.

"Tiny Grains" is on view in our Soho gallery from Sept. 18, 2024 through Jan. 12, 2025. Join us for the opening reception on Sept. 18 from 6 yo 8 PM. The accompanying book is available now.