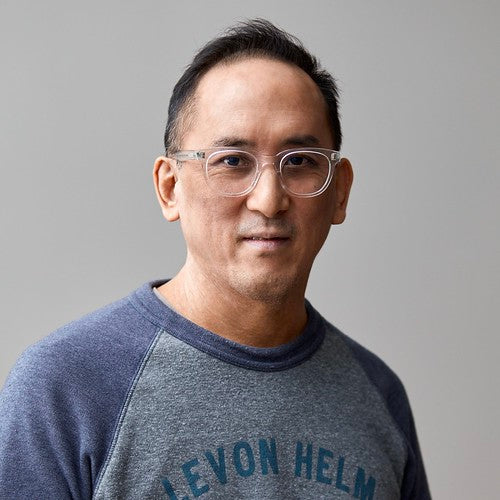

Artist-in-Residence Warren King: Connecting to a Community, Reconnecting to His Roots

The first time we saw Warren King’s life-sized sculptures in person, we were stunned. Not only were the works beautiful in and of themselves, we were astonished to know they were made from — not clay, terracotta, or wood — but corrugated cardboard and glue. We were looking forward to holding an exhibition with Mr. King in 2020, but the world changed, and it, along with many things, was put on hold, which makes us even more grateful to be able to host his show now.

"OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP: Finding Home in Chinatown" features some of his latest pieces and pays homage to his reconnection with his Chinese origins and culture, the resilience of nearby Chinatown, and those everyday people who anchor it. We had the chance to speak to Mr. King about the inspiration behind his show, how he began as an engineer, and how a seemingly simple question from his son sparked a whole new career.

Where is your family from? Where did you grow up?

My parents are from China and moved to Taiwan when they were little kids. They grew up there and after college came to the U.S. for graduate school. They ended up in Madison since my dad had job opportunities there, and that's where I was born.

It's funny. My dad loves to eat out and loves Chinese food, but he never considered living on either coast. He was always very focused on his career. So he ended up staying in Wisconsin working as a structural engineer. He designed parking decks and stadiums. The drive between Milwaukee and Chicago is like a tour of his life.

Where did you go to college? Did you study art?

I went to MIT. When I was growing up, I had an interest in art. I was a serial doodler. I took whatever art classes I could in high school, but it was never more than a hobby. I'm the oldest son so it was my destiny to take over my dad's company someday. As far as I could remember, I was going to do structural engineering, and that was that.

But I always had an aptitude in art. I got scholarships for summer art camps and always did art activities in school. When I was applying to colleges, my art teacher got a bunch of brochures for art schools, but I don't think I even brought it up with my parents.

Did you ever go through a rebellious stage?

No. It was never even a consideration that I wouldn't study engineering. When I applied to colleges, it was only engineering schools. At MIT I pursued a little bit of art stuff but nothing for credit. Just evening classes.

At some point I thought about doing something more creative. I thought, I'm studying buildings and structure. How about architecture? That's creativity combined with engineering. I brought it up with my dad, and it was a flat no. [Laughs] So I got a bachelor's in civil engineering and a master's in structural engineering in California. Then I went back to Wisconsin and started to work with my dad, building parking decks and hospitals.

After about a year and a half, the feeling crept up on me that I couldn't do this anymore. My dad could see it. The frustration. I thought, I'm just gonna live in a cabin in the woods by myself for the rest of my life. Then I made the big decision to leave. It wasn't easy. My dad took it badly. He was angry for quite a few years.

What did you do after you left?

I actually didn't know what I wanted to do. At the time it was the dot com boom. The technology was brand new. Companies didn't need people with deep experience, just those who were smart and willing to work long hours. By pure luck, I stumbled on this rising company and applied for a job. It was started by a couple of MIT guys. That was the beginning of a big rollercoaster ride. The company was based in D.C. and I was living outside New York. I was traveling to multiple places from Sunday until Friday or Saturday every week. I did that for three or four years. It was fun. I was working hard and it was just part of the dot com boom craziness.

Then I went to another company that was similar. It was based in California. I was in software for almost 17 years. Eventually I got really burned out. It was a lot of stress and a lot of work. So I took some time off. My kids were young at that time, and the break turned out to be longer than expected.

Then we had a chance to move to Sweden. My wife had a job opportunity there and we decided, What the heck? Let's just move there. We stayed for four years. It was a total life change.

How so?

At first we thought we'd be there for just a couple of years so I didn't make the effort to look for a job. The art stuff sort of came out of the blue. I don't think I could have done it anywhere else. In California were all our friends and colleagues, a whole life. You couldn't just suddenly do something completely different. For me it took being a new place to try something new. That's kind of how it got started.

I've always been really hands on with my kids. I was always building stuff for them like toys and masks for Halloween. Eventually I got pretty good at it. When teachers find out you have a skill, they start to ask you to help out. So they asked me to help with theatrical productions.

It wasn't until I was in Sweden that my son asked me, "Dad, why don't you make something for yourself?" I started to think about if I had to do something for myself, what would I do? What came to mind was tackling a human figure. I thought it was the hardest thing you could do.

I made one figure and was really happy with it. I made another. Soon I had two or three, which I put together, and suddenly I had a group that was communicating with each other. I thought, This is really interesting. Then I made more.

After a while I wanted to learn more about the art world and what being an artist really means. I rented a studio space in an artists' collective in Stockholm. It was 20 or 30 studio spaces in a basement. It was a shared space so that meant a bunch of working artists together. I met some really great people I've kept in touch with. They helped me learn about what it means to be an artist.

A benefit of renting that studio space was the gallery space up front. If you were a member, you could put on a show once a year. After I made a few of these pieces, I put on a little show. I had six figures by that time and no expectations, but people showed up. Other people started to talk about it. More people showed. The right people saw it, and a gallerist invited me to do a solo show. Another person invited me to do an art fair. And it snowballed from here.

I never really had a plan. I wasn't comfortable calling myself an artist. After a few shows and I had done a few things, then I started calling myself an artist.

Your pieces have such a distinct style. What's the influence behind it?

A lot of people use cardboard as a medium, but not many use it the way I do. I impose different rules on myself. I keep the feeling of the cardboard, going along the ridges, and use it in a way that feels natural. I only bend it along the lines, not the other way. I'm very constraining in the shapes that I can make. For instance, I can only make cylindrical shapes and not balls or spheres.

That dictates the style of pieces. It gives them a geometric look. Those constraints really appeal to me. Since my background is in engineering, I like the problem solving part of it, of having to work within these limitations. It isn't just about making something that looks good. If you have a hand or a face, there are only certain ways to shape materials. You have to creatively render that shape. You have to use tricks, like shadows, to imply what you're conveying. If your material doesn't allow you to make a rounded face, you have to make compromises. A jawline that I make isn't a really curved. It's using light and shadow to make a curve.

If you're using clay or wood, you can make any shape that you want. Sometimes I'm envious of someone who uses clay, who can come up with anything. The way I use cardboard, I have boundaries. It's a different kind of creativity. With clay, you can improvise a lot. You can adjust and change, in small ways, until you get what you want. With my process, when you have an idea, so much planning goes into it. It needs to be precise. There's not much room for improvisation. Once the glue is set, you're stuck with it. What I've done is build in steps to allow myself to improvise. For example, when I do a large or complicated place, I first use thinner cardboard that's easier to work with and quickly build a prototype.

It's a balancing act. If you focus on just the clean edges, on just the engineering aspect, then you lose that creativity.

You've mentioned how a 2016 trip to China and meeting people who knew your grandparents inspired a recent series. Can you talk a little about that?

Like I mentioned, I had always made masks and animals for my kids. When I first started to think about a project for myself, I decided pretty quickly I wanted to do a human form. Of course I didn't want to pick a random person. I thought, If I'm going to spend several weeks making this, who do I want to make? The trip to China had been a few years before and had been such a profound moment for me. I felt like I was put in touch with my roots. I spent a lot of time looking back at those photos and imagining their lives. Those folks had been on my mind since I went to China. Besides the people from my grandparents' village, I met with other relatives. That also left a profound effect on me.

I ended up making a dozen pieces all based on these family stories. I spent a lot of time researching and interviewing my parents, digging out these stories about different relatives and my grandparents. Growing up, my dad and grandparents — I don't understand why — were reluctant to tell these stories. My grandmother has so many! She never talked about any of them. Maybe they didn't want to burden us? I had to demand they tell us about these things. They were pleasantly surprised that I was interested and wanted to hear them.

The art work I made from their stories tied my family members to myself. The experiences of my ancestors and relatives made their way through time and reached me and shaped my life.

When I was growing in Wisconsin, there wasn't much of an Asian community. I had never had much of a connection to my Asian roots. In fact I was in denial about them. It wasn't until much later, until after I finished college, that I really started to become interested in this stuff. The trip to China with my parents really woke that up. These last few years, I've been getting back in touch with these stories and roots, and reintegrating them into my life.

How do your parents feel about your art now?

They're very supportive now. My dad would have never supported my art when I was younger. After I left his company and jumped into the crazy intense environment of software startups, he said. "Well at least he's not lazy." I did well in that field and he was proud of that. Seventeen years later, he was finally ready to admit I could take care of myself.

When I started this art stuff, he didn't really know what was going on. But after articles were written about me, my dad was the proudest. He was always bragging to his friends, saying, "You should follow your dreams." [Laughs]

Why do you think your exhibition is a good fit with Pearl River?

I couldn't imagine a better fit. At this point I still don't think of what I do as an art career or as part of the art world. It's really a personal thing. I use this stuff to get in touch with a part of myself.

Like the trip to China, living near Chinatown has been revelatory for me. A couple of times a week, we go in to do our shopping and just walk around. I love seeing the regulars, the community, multiple generations, living and thriving. I get so much out of just walking to the park or buying groceries.

This series of works that will be shown at Pearl River is based on all that. Seeing people who remind me of my parents and grandparents. I get to know them in a unique way — by building a sculpture, spending weeks studying gestures and expressions.

Chinatown is a source of inspiration for me, and Pearl River is iconic in Chinatown. It's being run by multiple generations and had helped build the community. Showing my stuff at Pearl River means a lot. I know that people who come to see it won't just be art people but people in the community.

What do you hope visitors get out of your exhibition?

People ask me why I made this series. Am I trying to raise awareness and show solidarity? Yes, but the initial reason is connecting with these people. Sitting for hours a day and studying these people gives me a feeling of intimacy that's very unique. I feel privileged to do that.

I hope it comes through. That people see and share my affection for these people, and see them for how they are. So the next time they go to Chinatown, they'll notice them and see them in a different way.

OUR ROOTS RUN DEEP is on view in our SoHo gallery from Jan. 12 through April 23. Free and open to the public every day between 11 a.m. and 7 p.m. Join us for the opening reception on Jan. 12 from 6 to 8 p.m. Attendance is free but registration is required.