Artist-in-Residence Kam Mak: Re-Enacting Memories, One Eel at a Time

Whether you’re a snail-mailer or philatelist, you might be familiar with the United States Post Office’s latest Lunar New Year series, from the red lanterns of the Year of the Rat to peonies for the monkey year to the most recent gorgeous rooster. But do you know about the artist behind those stamps?

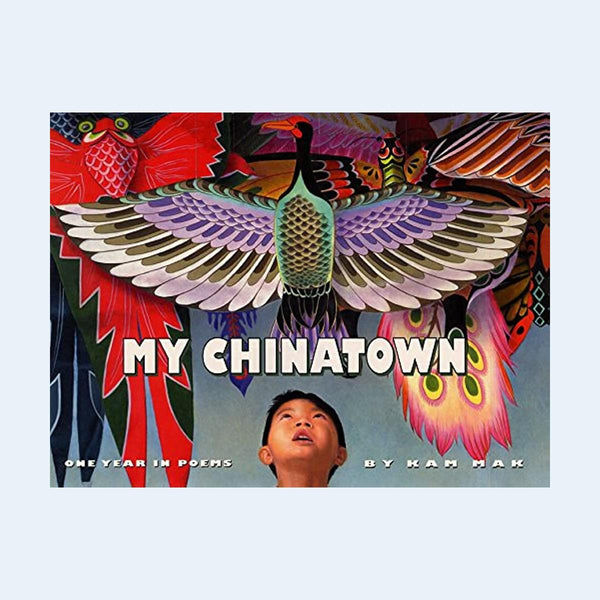

Kam Mak is an illustrator, painter, and professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), School of Art and Design. He’s also our latest artist-in-residence. Like his USPS commission, his exhibition at Pearl River explores animals, but you won’t find any of these on a postage stamp. His realist oil paintings depict eels, snails, pigs, and more — some live, some dead, all food.

We had the chance to talk to the New York native about the power of memories, students as inspiration, and why a headless chicken doesn't make a worthy offering.

I understand you came to New York from Hong Kong in 1971. How old were you then?

I was 10 years old. I came with my parents and four sisters — I’m the second of five kids — through my aunt on my mother’s side. We took advantage of the immigration change in the ‘60s that allowed for a larger quota of Chinese people. My uncle who’s been here since the ‘50s and lived in the Bronx, had a rent-stabilized apartment for us.

I still remember that time very clearly. It was early September, right before school started. I remember all the taxis and the BQE. I even remember the address — number 5 Eldridge Street. It was first tenement building on that street. We lived on the second floor. The floor wasn’t level and the bathtub was in the living room. I heard the train humming all the time. Maybe it bothered me at first, but I got used to it. In fact it helped me fall asleep.

What did your parents do after they came here?

I was just old enough to understand it was really hard for them. My mother worked in a sweatshop 12 hours a day, six days a week. My dad was a dishwasher. It was really difficult for him. He wasn’t used to this kind of work. He had a freer mentality. He worked on a cargo ship most of his life and did a lot of traveling. He loved that although we’d see him only a few times a year.

He went to the [1964] World’s Fair in Queens. Another time he came home with a used TV. All the neighbors came over and watched it.

Why did your parents decide to come to New York?

My mother was worried about 1997 [the year Hong Kong would be handed back over to mainland China]. She was looking way, way ahead. She didn’t trust the Communists and wanted a better life in America.

The saddest thing was leaving my grandmother behind. She had raised me and my four sisters when my mother was working. Unfortunately we never got to see her again. Less than a year after we got here, we got a telegram saying she had passed away from a stroke.

Did you suffer from culture shock when you first arrived?

It was a huge culture shock. I didn’t speak a word of English. The first year was hard. I got picked on a lot, especially by Chinese kids who were born here. So I ended up sticking with other immigrant kids.

I was a really bad kid. [Laughs] School was difficult so I’d play hooky. I’d take the subway with my friends to Coney Island and Flushing Meadow Park during the school day. Then my mother would get a notice and I’d get sent to the principal’s office.

My mother realized no one was supervising us so she put me in an afterschool program from the Chinatown Planning Council. They kept you busy. You could get help with your homework, play sports, and meet other kids. They also gave us snacks I didn’t have at home, like chocolate donuts. The teachers were really nice. They took us ice skating. I had the chance to do things I otherwise wouldn’t have.

When did things really start to change for you?

Junior high. It was at that time that I realized I couldn’t continue doing what I was doing. I saw friends die. They had joined gangs. One was shot in the back of the head in a theater.

One of the biggest worries was being grabbed by gangs to be recruited. You had no choice. Growing up, you heard about people just disappearing. At 10 I saw someone get shot. I thought they were playing but it was real. You grow up really quickly. You see a lot of things. In my last year of middle school, I started to study hard and totally turned around. I was definitely scared straight.

But it was a happy time too. I knew all my neighbors. We played hopscotch and kick the can. In the fifth grade I got hold of a bicycle. You know, with a classic banana seat. I was able to get out of Chinatown on that bicycle.

When did you first become interested in art?

Even as a kid in Hong Kong, I always drew. I would doodle in class instead of listening to the teacher. I’d get punished and they would make me do the invisible chair. [Laughs]

In the U.S. I had art class and really excelled at it. Even though I was really bad in math and English, in art class I was able to do really well and to communicate through my art. My teacher gave me a lot of positive encouragement and I grabbed hold of it.

I felt like I had something other kids didn’t have. I was so bad at other things. Finally, I had one thing I was good at and that I enjoyed.

My art teacher also helped me with my portfolio for a specialized art high school. I was lucky to have her spend her own time to help me. As a result, I got into LaGuardia High School [Of Music & Art and Performing Arts].

That was culture shock too. Between Hong Kong and Chinatown, I had grown up with people like me while LaGuardia was up in Harlem and had students from all over New York.

How did your parents feel about your going to a specialized art high school?

My mother had no idea what the school system was like. She wasn’t really concerned that I was going to art high school. She thought I’d grow out of it and would do something more professional in college.

Later my mother told us there was no money for college, and we had to fend ourselves. I looked for a state school. Then my teacher told me some schools give full scholarships. I applied for one with SVA [School of Visual Arts]. There were over 5,000 applications, and I got the scholarship. My mother finally realized her son was going to art school. She freaked out and tried to convince me not to go. She cried a lot, saying, “You’re going to be a poor artist!”

But I was pretty stubborn and decided to go. I didn’t want to let my mother dictate my future.

How did you like SVA?

I had a great time. I loved getting to meet professionals in the field. By my third year in college, I knew I wanted to be an illustrator. I really worked at perfecting my craft. I got a job while in college: a cover for Newsday. Out of school I spent all my time pursuing an illustration career. Of course my mother wanted me to get a regular job. She said get an application and get a job at the post office.

In a way, you did! [Mr. Mak has been illustrating the U.S. Postal Service’s Lunar New Year stamps since 2006.]

[Laughs] You’re right!

As for my mother, I know she only did those things because she was worried. She didn’t want me to struggle. When I was younger I didn’t understand that. I just thought she was against me. So after 18 months of living at home, I moved out. I needed a more positive environment. I moved out with a roommate from SVA, which was the best decision I ever made.

I lived check by check. My mother helped with getting me rent-stabilized apartment, which was was very cheap back then. I had short-lived odd jobs here and there. I assisted other artists but that was difficult. I wanted to be the artist, not the assistant. But I just kept working, and by word of mouth and self-promotion, I kept getting illustration jobs.

Now you’re also a professor at FIT. How did you get into teaching?

I started teaching around 1998. I taught at SVA for two years. I took over a painting class that my teacher gave up. I enjoyed it. Those two years gave me a lot of experience.

Then my two younger sisters who were going to FIT said why don’t you get a permanent job here? I got a job quickly. It was good timing. A couple of professors were retiring. I’ve been there ever since, 24 years now.

Do you get a lot of inspiration from your students?

I really do! I’m the artist I am now because of my students. I’m even more inspired by them now that I’m older. I learn more from them than they learn from me. It’s this energy they have — I’m just trying to keep up with them.

Something interesting about students now is that, because of the Internet, they have a lot of knowledge and know a lot of things. But they don’t necessarily know how to do things. Also, there’s no barrier between the professor and student. Sometimes they email me in the middle of the night! When I was younger, I would never call my teacher! Now it’s so different. There’s this sense of entitlement to have access to the professor. I have to teach my students etiquette. Some get frustrated when you don’t respond promptly, but many are very respectful.

Speaking of inspiration, is there something in particular that's inspiring you right now?

My biggest passion right now is egg tempera. It’s something I learned about eight years ago. It’s really difficult. It was the medium of the Italian Renaissance. The painters then were masters of it. Then it disappeared.

Now some famous contemporary artists like Andrew Wyeth and George Tooker use egg tempera. They really inspired me to pursue this technique.

What is it about egg tempera that attracts you?

The color. It’s so vibrant. Not shiny but so rich. All it leaves behind is the pigment. It’s very luminous. I had the chance to go to Italy and look at the masters. Like Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. A lot of those skills are lost. They know some of how it’s done but not everything.

I’m very excited about your exhibition for us. What was the inspiration behind it?

That started more than 10 years ago. I have wonderful memories of going to the market with my grandmother in Hong Kong. As a city boy, I didn’t get to see nature and animals. I got hooked by going to the market and seeing these animals, still alive, still moving. I grew up in part of Hong Kong right next to ocean. The street beside the ferry was full of seafood places with tanks filled with beautiful fish. As a kid, I was fascinated by these living things.

My obsession continued even after we left. I have this painting of dead ducks that was inspired by this memory I had while I was in high school. I worked in the basement at Hop Lee, marinating char siu, and the chef would air dry the ducks. They looked like human bodies. So fleshy and interesting to me. I wanted to re-enact the memory in a painting.

When I was younger, I didn’t understand my obsession. It was just about the visual. But now I realize it’s more about the culture. Where does our food come from? Chinese people like food to be intact. You can’t offer a headless chicken to the gods! It’s part of the culture, part of life. You don’t think about it.

My attraction to that imagery will last me the rest of my life. This will be a never-ending series.

So you’re not a vegetarian, right?

Oh no! I love meat! Some of my students drive me crazy. They’re vegan. They go to Italy and can’t eat anything.

I know in terms of the exhibit, everyone will have a different reaction. It will be tied to their own experience. Some people might be grossed out. And Chinese people will still appreciate it, even if they don’t know about art. They’ll find something familiar about it, that they can relate to.

From Tank to Palette is on display in our mezzanine gallery from October 6 through November 11, 2017. To see more of Mr. Mak's work, visit his website or follow him on Instagram.