Sweet White, Blood Red, and Blue and White: An Emperor’s Prized Porcelains

You might have noticed we have a thing for ceramics and porcelain (a kind of a ceramic). From traditional Chinese patterns to pretty blossom designs to classic blue on white, we love them all. But there’s something also to be said for a sweet and simple white. That got us thinking about “sweet white” porcelain of another variety, namely the imperial kind.

The Yongle emperor: powerful, effective, porcelain-loving

Some describe the Yongle emperor as “the most powerful, effective, and extravagant ruler of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).” Ruling between 1403 and 1425, he was the fourth son of the Ming dynasty founder, the Hongwu emperor. While Yongle first approved of his father’s appointment of his nephew as emperor, he rebelled when his nephew began executing and demoting his uncles.

Thus began an ambitious reign. He moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, where he directed the construction of the Forbidden City; pushed the Mongols back into Mongolia; expanded his empire into Vietnam; and sent maritime expeditions reached as far as the east coast of Africa.

But his true love might have been porcelain. “Pure and lustrous,” he called it, and “indeed pleasing to the heart.” During his reign, three main types were popularized, improved upon, and innovated: blue and white, blood red, and sweet white.

Blue and white

Dating back to the Tang Dynasty, blue and white ceramics had already been around for hundreds of years before Yongle took the imperial seat. However, under his reign, the types of decorations were greatly expanded.

Motifs with fruit, flowers, and plants were the most popular:

"Plate with Rocks, Fruits, and Flowers." Metropolitan Museum of Art

There was also Islamic influence —

"Flask with Medallion," Metropolitan Museum of Art

as well as Tibetan —

"Altar bowl with Tibetan inscription," Metropolitan Museum of Art

— as the Yongle emperor was a patron of Tibetan Buddhism.

After the Yongle reign, blue and white porcelain only continued to increase in numbers and popularity.

Blood or sacrificial red

"Plate with Bright Red Glaze" by Rosemania (CC BY 2.0), Palace Museum, Beijing

Like blue and white, the jihong or blood red design was developed during the Tang dynasty. It came about accidentally: bronze was often used to make porcelain green, and was found to turn it red instead when fired under different temperatures.

Under Yonghe, the technique was improved so that the coppery red became more brilliant. Later, such porcelain was often used in sacrificial ceremonies and thus gained the name “sacrificial red.” Notoriously difficult to produce, jihong is the rarest of the three.

Sweet white

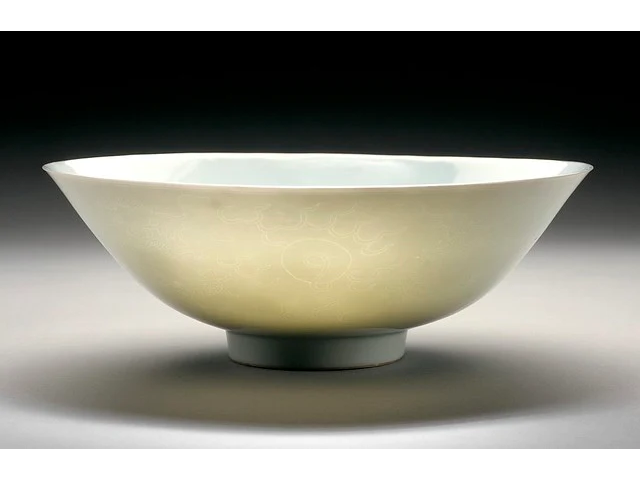

“Bowl with Dragon and Clouds,” Cleveland Museum of Art

The Yongle emperor’s personal favorite was “sweet white” or tian bai (甜白), so called because of its resemblance to sugar. Inspired by shufu, another type of white ware produced during the Yuan dynasty (1206-1368), the sweet white technique was innovated under Yongle. Its thick glaze was characterized by small “orange peel” waves and “hidden” decorations only made visible under light.

The Yongle emperor was so enamored with sweet white porcelain, he commissioned the building of a pagoda covered in white porcelain bricks in Nanjing along the Yangtze River. Considered one of seven wonders of the medieval world, its construction took 17 years and was unfortunately destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion in the 19th century. In 2017, the pagoda was rebuilt and opened to the public.

Feeling porcelain happy like Emperor Yongle? Check out our whole ceramics collection.

[Lead image: “Bowl with Dragons Chasing Flaming Pearls,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art]