Chinese Weddings Traditions, Past and Present

Every culture has unique wedding traditions. An African American bride and groom might “jump the broom" to symbolize their union. German newlyweds might saw a log in half to represent their first challenge as a couple. An Indian bride's sisters might steal the groom's shoes for ransom.

Chinese weddings have their own traditions, from complex ancient rituals no longer practiced to contemporary customs you might want to incorporate into your own Chinese-inspired wedding. Here are nine of them.

Setting a lucky date

To determine an auspicious date for the wedding, fortune tellers analyzed the dates, days, and times the bride and groom were born. But if you don’t want to go all that trouble, at least avoid the last 15 days of the seventh lunar month, otherwise known as the Hungry Ghost Festival. The last thing you want are famished phantoms at your banquet.

An attic retreat

In old China, once a woman married, she often left behind her family and friends. Hence this tradition of of an extended sleepover with her closest female friends. Called "retreating to the cockloft," this took place in a separate part of the house such as the cock loft, another name for a small attic.

The bride’s besties showed how much they cared by singing songs mourning her departure and cursing the matchmaker, the groom’s parents, and even the bride’s.

The "hair dressing" ritual

In the wee morning hours of her big day, the bride bathed in water infused with pomelo, similar to grapefruit and effective as both an evil influence cleanser and skin softener.

A “good luck woman” — one blessed with a good marriage and healthy family — was employed to speak auspicious words while dressing the bride’s hair in a married woman’s style.

The bridal gown

In olden times, the bride stuck with one outfit: a jacket, skirt, and veil, all in lucky red, which symbolizes success, loyalty, honor, and fertility. In contemporary weddings, the bride might change several times. While white is traditionally an unlucky color (it symbolizes death), modern brides often opt for a Western-style gown for the ceremony, changing into a traditional qipao and possibly a cocktail dress during the reception.

The procession to and from the bride's house

While today the ceremony and reception are the focus, back in the day the procession was the main event.

The groom led the one from his house in the wake of firecrackers, gongs, and drums to scare off evil spirits. Also in tow were the bridal sedan (to carry the bride natch), attendants with lanterns and banners, and a dancing lion. When the groom’s party arrived at the bride’s house, the bride’s friends refused to “surrender” the bride until they received sufficient hong bao, or red envelopes full of money.

Firecrackers also paved the way for the journey from the bride’s house back to the groom’s. The sedan chair was curtained to prevent the bride from seeing “inauspicious signs” such as a widow or a cat.

The tea ceremony

Unlike today, wedding ceremonies of yore were simple. At the family altar, the bride and groom paid homage to heaven and earth, ancestors, and the Kitchen God, which protects the hearth and family. The couple then served tea to the groom’s parents, then bowed to each other.

Nowadays the tea ceremony is often incorporated as a special homage to both sets of parents, whether before, during, or after the main ceremony and festivities.

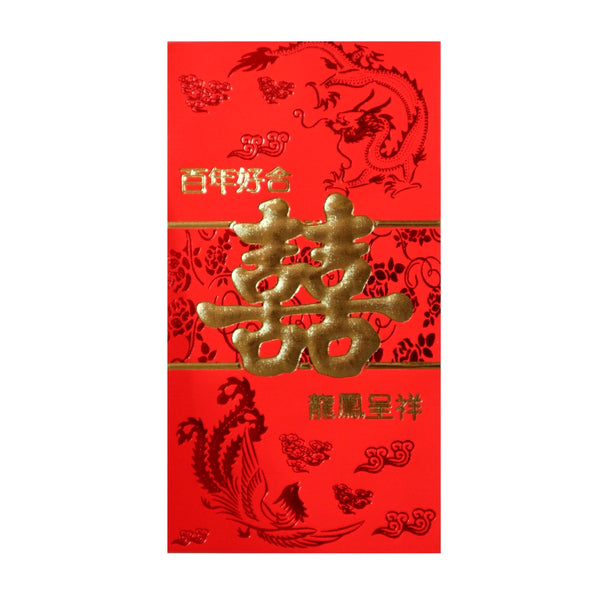

Double happiness

This special character — made up of twin xis, the character for “happiness” — is used specifically for marital bliss. Pronounced shuang xi, the double happiness symbol might appear on invitations, decorations, and even cake.

The banquet

Once upon a time, multiple banquets were given. The parents of the bride and groom hosted separately, often several times over several days. But the main banquet was given by the groom’s side on the day of the wedding, similar to today’s practices.

Like the food served during Lunar New Year, each dish at a Chinese wedding banquet has significance.

Shark fin soup. This expensive delicacy was once a mainstay in Chinese wedding banquets, but some states have banned it due to inhumane practices. There are plenty of alternatives, however, including sea cucumber (itself a good wedding food since the Chinese word sounds like “good heart”), bird’s nest soup with seafood stock, and mung bean.

Roast pork. Apparently a symbol of virginity. Sometimes the groom offers a whole suckling pig to the bride’s family. More commonly, a barbecue pork platter is served.

Peking duck. Not only is Peking duck delicious, it’s lucky due to the reddish color of its skin. Preferably served with its head to symbolize completeness.

Lobster. Another lucky red food, and again, best served whole.

Squab or quail. These tender game birds symbolize peace.

A whole fish. In Chinese the word “fish” sounds like “plentiful.”

Red bean soup with sticky rice balls. This mildly sweet dessert marks a sweet ending to the banquet and sweet beginning to the newlyweds' lives together. Today western-style wedding cake or another dessert might also be served.

Alcohol, tea, and 7-Up. What’s a wedding without alcohol? Plus the Chinese phrase, “going to a dinner banquet,” is synonymous with “going to drink alcohol.” Meanwhile, tea is served as a sign of respect and 7-Up is a favorite because the name sounds like “seven happiness” in Chinese.

Games

In the ancient tradition of the bride’s friends refusing to “surrender” the bride until they received enough hong bao, some modern bridesmaids practice chuangmen before the reception or banquet.

The game involves posing a series of sometimes painful challenges to the groom and groomsmen before the groom can see his bride. The men might be asked to do anything from innumerable push-ups to eating spicy foods to waxing their legs.

The banquet itself can get quite raucous with naohun, a series of ribald games designed to stir things up. A tamer one involves men kissing the blind-folded bride on the cheek while the bride tries to pick out her husband. In another, the bride and groom eat strung-up cherries without their hands.

Gifts

Ancient gift giving traditions were complicated. Even before the wedding, proposal and betrothal gifts were exchanged between the two families. The day after the wedding, the bride received small gifts from the groom’s older relatives as an official welcome.

Nowadays you can’t go wrong with cold hard cash, preferably in a hongbao. But you should avoid denominations of four (a homonym of “death”). Multiples of eight are good, especially 88 which bears a striking resemblance to shuang xi, and nine, which sounds like “long,” as in a long and happy marriage.

[Photos CC BY 2.0: "Chinese Restaurant Wedding Reception" by Kenneth Lu; "The Beautiful Bride" by Cormac Heron; "Traditional Chinese wedding ceremony" by kanegen; "Wedding feast" by Micah Sittig]